|

Weston was a US company but it quit making meters domestically around 1960. After that they imported them in from their English sister-company Sangamo-Weston. Weston was a US company but it quit making meters domestically around 1960. After that they imported them in from their English sister-company Sangamo-Weston.

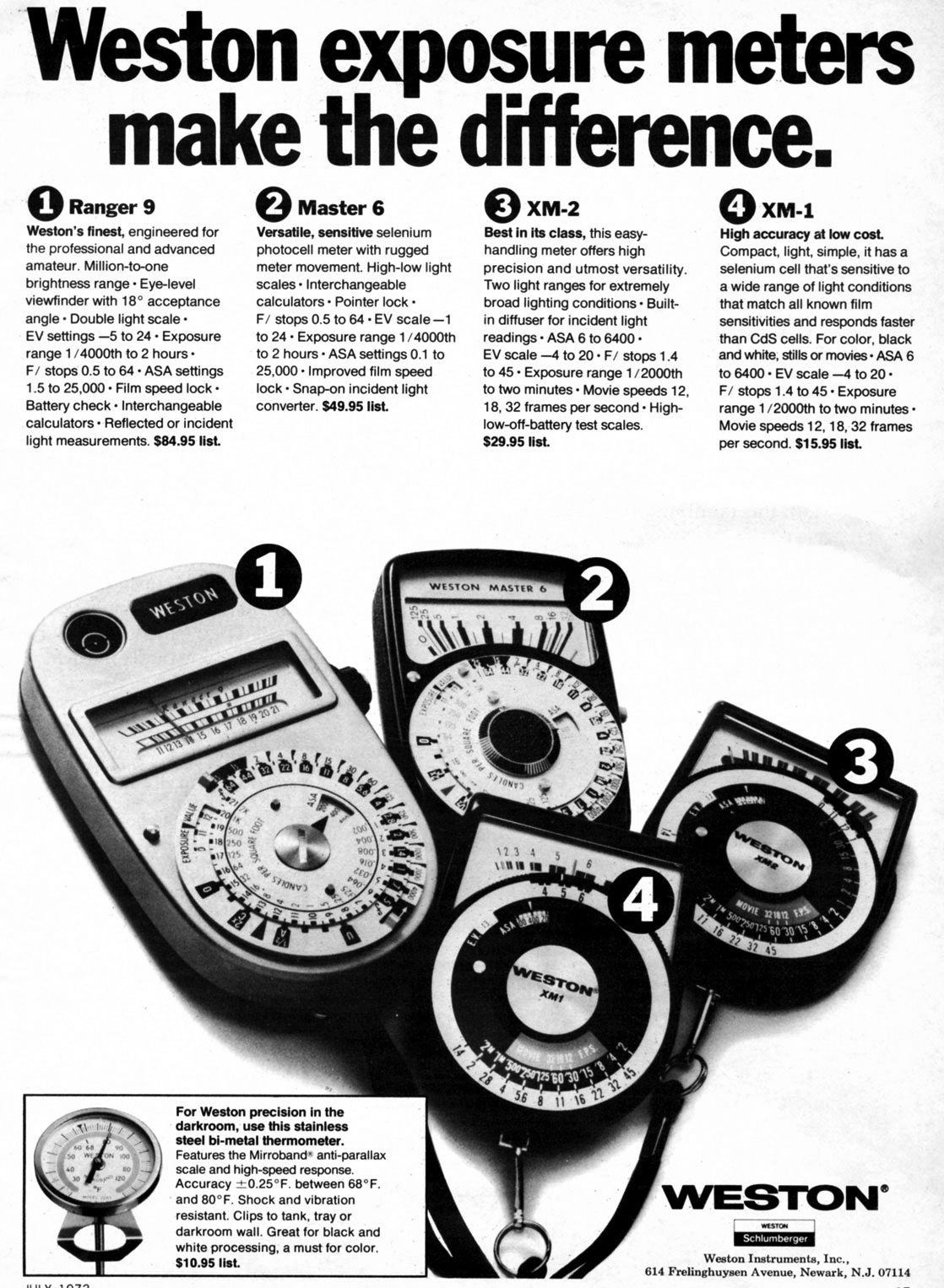

By the early 70s, however, Weston pulled out altogether and simply licensed their name. The Brits kept the Master V alive with the Euro-Masters, but the Japanese built three new meters under the Weston name. They were the Master 6, the XM-1 and this XM-2.

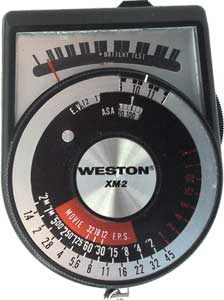

The Master 6 was meant to continue the Master series, but the XMs were new and different. They were simple meters, just a pointer, a needle and a calculator dial. The XM-1 used the old selenium cell, the XM-2 was nearly identical but used CdS.

One of the big problems with it is obvious: it looks cheap. The original Westons were considered quality products. Even their budget line, direct readers were thought to be good meters. It's like buying a budget Ferrari that looks and acts like a Ford Taurus. Few people will buy it—most people who care will be saddened by it.

If it didn't say Weston, it might have fared better. It's actually a nice little meter. It fits the hand nicely. The thumbwheel on the side turns the meter on, off, sensitivity scale and battery check. The calculator is simple and easy to use. It has a built-in slide switch in the front that flips between incident (via a little 3D hemisphere) and reflected light.

Actually, elsewhere in the world it did have different names. It was sold as a "Shepherd AM 130", for instance, and also as a Photopia S-EM in Europe. The 1977 Sears Camera Catalog lists it as the "Sears Exposure Meter" (p.35). There's also a Hama floating around.

So who made it? Modern Photography magazine actually reviewed the XM-1 and XM-2 in their May 1972 issue, and they claim that Sedic made them. Sedic made a variety of meters under their own name, but more often made for house-brands like Boots, HAMA, and Hanimex.

Modern also gave them a good review. See below.

Weston, the grandpappy of all photoelectric exposure meter manufacturers [J. Thomas Rhamstine would have something to say about that.—James], took a careful survey of the low- and medium-priced small hand-held meter field, and found that it was alive and healthy but Weston wasn't in it. From the

specifications you might reason that Weston forthwith entered this part of the field with two very me-too, look-alike units which could promptly get lost in the big pile of small hand-held meters.

Far from it. Actually made for Weston in Japan by Sedic Ltd., both Weston entries have very respectable qualifications and are vastly different from each other, although they are exactly the same size, shape and have exactly the same calculator dial. Is this possible? Read on.

How would you lke a meter that required not battery, had a better spectral response than CdS meters and was compact enough to slip into a shirt pocket? That's the Weston XM-1, which uses a selenium cell meter circuit instead of CdS. Admittedly, the CdS cell is bette for reading in low light or for use in through-lens meters or spot metering situations. But for fairly high levels of illumination nothing has yet equaled the selenium cell. Of course, Weston still does have its famous selenium cell Weston V, but that is hardly a quick-acting low-priced shirt pocket meter. The far lower-priced XM-1 proved extremely accurate. Using our Zelox testing unit, we found that it could read within 1/4 stop of a known light source down to 1/60 at ƒ/2.8 with a film having an ASA of 400. If you're an outdoor-mostly photographer, this would be an excellent aid—and look, no batteries!

Although the meter is 3 in. long and 2 5/16 in. wide, it is but 5/8 in. deep, excvept for the raised dial area, which adds another 3/16 in. It can slide into any nook or cranny and yet, by not skimping on the length and breadth, this hand-held meter has large, very easy to read scales and dials.

The pointer scale has 10 numerals well spaced centrally but rather squeezed together at the high and low ends. You point the meter, read off the nearest numeral, transfer the numeral to a cutout window on the calculator dial and read off all possible shutter-speed/aperture combinations on the opposite side of the dial. While there are blocked out areas between the numerals on the pointer dial which could be used for in-between readings, there are no between full ƒ/stop markings on the aperture-shutter scale (although you could possibly interpolate them if you wish). Obviously, Weston felt that an uncluttered, easy-to-read dial with large numerals was preferable for this meter to a more comprehensive dial with smaller figures or between marking points.

The look-alike XM-2, with its PX-13 mercury battery powered CdS circuitry, is for the photographer who will need exposure calculating help in low light. It has a dual scale which works very much like the traditional Weston V. In bright light the pointer sweeps over a scale reading from 8 to 16. By revolving a circular inset switch on the right hand side, the scale shifts to low light numerals from 1 to 9. Numerals on both high and low scales are mor equidistantly spaced than on the XM-1. Calculating your exposure is done precisely in the same manner as with the XM-1. The XM-2 tested with our Zelox equipment could read down to 1/30 sec. at ƒ/2 with an ASA 400 film, maintaing an excellent accuracy of within 1/4 ƒ/stop. However, the meter can read down further to 1/8 sec. at ƒ/1.4 within 2/3 ƒ/stop.

Besides the high and low scale shift, the circular switch also has battery check and off positions.

The very small incident light sphere which slides over the cell on the front we judged to be usable for uncomplicated lighting situations in which the angle of illumination wouldn't be too acute for the small cell to gather. It obviously isn't any ideal substitute for the incident sphere of a Weston V or a true incident reading meter needed for studio lighting seetups.

Both meters are very nicely designed with plastic housings, can be operated swiftly and conveniently with one hand, are carefully put together and come complete with soft zipper pouch cases and neckstraps. We preferred, however, to fasten the neckstraps to the meter and discard the cases, which would have added bulk to these instruments.

The only thing we did not like about thes meters were the instruction booklets, which did tell you how to operate the controls mechanically, but gave no hint on how best to use the meters for specific lighting situations—shame on you, Weston!

|