My first job was working for a department store. I was in the business office and we had printing calculators because every so often we had to run tapes. I learned how to 10-key, and even then I had developed some speed.

One day one of the calculators broke, and the boss said to go out to the Electronics department and buy another one out of petty cash. We were a department store: we didn't sell professional office machines, we sold consumer products. All we had were TIs, so I got one and tried to use it. It was awful.

Now I like Texas Instruments, but that printing calculator was never designed for office work—it was for a guy doing his taxes at home or selling children's clothes at a garage sale, where he'd tap the buttons with his index finger. It could not keep up with anyone who could 10-key at all. The printer lagged and it would throw off your rythmn, and then you'd either screw everything up or have to stop every 3 seconds to let it catch up. I couldn't throw it in the trash because the only alternative was another one.

The good ones we had were Victors, and I realized I had taken their performance for granted because I'd never used anything else.

Years later and I'm with another company, and again my old printer-calc had to be replaced. The boss said to get the office supply catalog and order one. I got a Victor (a model 1560) and never regretted it. It was expensive, but it keeps up. I've had it 15 years now without a hiccup. I have a thing for Victor adding machines.

Every once in a while I thought it would be fun to get an old adding machine for my office. The problem was that I would only see them an antique shops, usually looking like they'd sat in a basement for the last 40 years, with bald spots in the paint and missing parts, priced at $100. Months or years later I'd come in and it would still be there, with little dust rings around the feet because it never been touched. Maybe the price tag had been marked down to $89.50.

On an online auction site I frequent, they seem to be sold by the pound. If I had the room, I could build an impressive collection in little time, and for a hell of a lot less than a typewriter in the same age and condition. Of course you can't type a note to Tom Hanks on an adding machine, unless you want to do it in Octal with a transposition lookup table. Thought not.

Anyway, once I realized this, I found these two old Victors. Why pick these? Well, for one: they're Victors, my favorite calculator brand. For another: they had something most of the others lacked—curb appeal.

Most adding machines I've seen from other companies, including Victor before and after these models, are styled as very functional and dull. Most earlier machines, including those from Victor's competitors, look like they were made from leftover typewriter parts. Later machines tend to resemble desktop telephones. That makes them kind of "fit" on an office desk, but I admire a little panache in my office products.

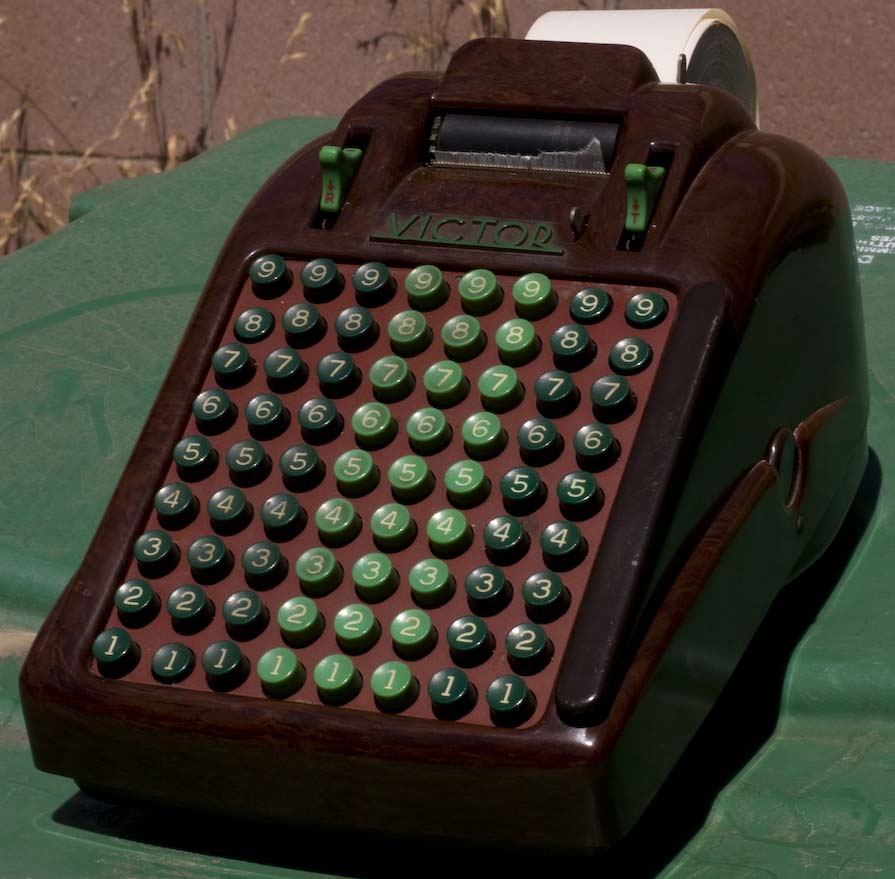

I'd like to say that I bought them purposely because they were a matched set of opposites (so I'm going with that). The first one is a 600 series, which means it has the "full keyboard" style. They came in several versions: 5-, 6- and 8-columns. The first two columns on the right are for cents, the rest determine the largest number you can enter; a 5-column machine would top out at $999.99, which for many businesses during the Depression or War years was probably more than you'd ever need. An accountant in the back office or at a larger company might need the extra columns, which would get you up to $1M an entry. The calculator could actually go higher, because what happens if you add $999,999.99 twice? Three time? More? The columns limited the highest amount you could enter, but the top tally on this machine was 4,999,999.99.

I'd like to say that I bought them purposely because they were a matched set of opposites (so I'm going with that). The first one is a 600 series, which means it has the "full keyboard" style. They came in several versions: 5-, 6- and 8-columns. The first two columns on the right are for cents, the rest determine the largest number you can enter; a 5-column machine would top out at $999.99, which for many businesses during the Depression or War years was probably more than you'd ever need. An accountant in the back office or at a larger company might need the extra columns, which would get you up to $1M an entry. The calculator could actually go higher, because what happens if you add $999,999.99 twice? Three time? More? The columns limited the highest amount you could enter, but the top tally on this machine was 4,999,999.99.

I have no evidence for this, but I would bet lunch money that you could special order machines that moved the decimal over to four or six places if you needed it. Just like you could get one for foreign countries that swapped the comma and decimal markers.

Full-keyboard machines started, I believe, with Burroughs in the late 19th century, and ran until the 1950s, maybe 1960s, when 10-key finally took over. That's my other model: a 700 series 10-key machine. They basically do the same thing, only the entry method was different. If you were Bob Cratchit in the early to mid 20th century, you learned one touch method or the other, and Scrooge had to pay you for it because it was a worthwhile skill, like being able to touch type.

These two have another matched-set feature: you could buy either of them as a manual (you tap in your figure and pull the crank to print it), or electric (you tap in your figure and press that long vertical bar to the right to print it). Scrooge would prefer manuals because they don't take electricity, but electrics are faster in the long run; if you're doing production work, adding long lists of numbers all day, electrics pay off. Regardless—I have one of each.

These two have another matched-set feature: you could buy either of them as a manual (you tap in your figure and pull the crank to print it), or electric (you tap in your figure and press that long vertical bar to the right to print it). Scrooge would prefer manuals because they don't take electricity, but electrics are faster in the long run; if you're doing production work, adding long lists of numbers all day, electrics pay off. Regardless—I have one of each.

Both of these machines were made about the same time (late 1940s): these models ran concurrently for decades because a lot of people were trained on full-keyboard, but many other people wanted 10-key; some would pay the added expense for an electric motor, which others wanted the reliability of a crank.

I believe they also came in different case colors; likely black and gray. I assume these swirly-brown models are either for executives or other people who were willing to splurge on having a good looking office machine, rather than something that was purely functional. Even then, the two models I have are similar but not the same. The full-keyboard model is medium brown and the swirl is much more pronounced. The 10-key is much darker, almost black. In bright light you can see brown swirls, but it's very subdued.

_SEP.jpg)